|

|

AbstractAmyloidosis is a rare benign disease characterized by the extracellular deposition of nonsoluble fibrillar proteins (amyloids) within organs. Laryngeal amyloidosis (LA) accounts for only 9%-15% of all cases of amyloidosis. Since clinical manifestations and laryngoscopic findings often overlap with those of laryngeal cancer, it is challenging to differentiate LA from laryngeal cancer prior to surgical biopsy. We report a case of LA mimicking laryngeal cancer, in which the diagnosis was facilitated by preoperative ultrasonography (US) and US-guided core-needle biopsy (US-CNB) prior to surgical biopsy. The US findings of this case were distinguishable from those of laryngeal cancer, which enabled us to consider a diagnosis other than laryngeal cancer. Amyloidosis was diagnosed preoperatively using office-based percutaneous US-CNB, avoiding general anesthesia needed for suspension laryngoscopic examination. This case suggests that US and US-CNB could be used as supplementary diagnostic modalities to evaluate suspicious laryngeal masses mimicking laryngeal cancer.

IntroductionAmyloidosis is a rare benign disease characterized by the extracellular deposition of nonsoluble fibrillar proteins (amyloid) within organs [1,2]. This abnormal protein can be deposited anywhere in the body and can have either a localized or systemic distribution [2,3]. As one of the localized types, laryngeal amyloidosis (LA) accounts for 9%-15% of all cases of amyloidosis and represents only 0.2%-1.2% of all benign laryngeal tumors.2,3) Although it can be located anywhere in the larynx, the most common primary subsite is the false vocal cord [1-3].

Clinical manifestations of LA usually begin with a nonspecific cough and foreign body sensation, and may involve dysphonia, dysphagia, and dyspnea as the disease progresses [1,3]. Laryngoscopic findings of LA vary depending on its location and extent. LA can present a wide range of abnormal findings, from a localized mass to diffuse laryngeal swelling, often associated with vocal cord paralysis in advanced stages [1,2]. As these signs and symptoms along with laryngoscopic findings overlap with those of laryngeal cancer, it is challenging to differentiate LA from laryngeal cancer without biopsy results [4].

To facilitate preoperative diagnosis of LA by excluding of malignancy, several studies have evaluated the characteristics of LA on cross-sectional images [5-7]. On CT, LA reportedly appears as a well-defined, homogenous, and low-attenuating mass with occasional punctuated calcifications [6]. MRI is regarded as an ideal modality, which demonstrates the characteristic intermediate signal on T1 comparable with that of skeletal muscle, enhancement with contrast, and a low T2 signal reflecting the low water content [3,6]. However, these CT and MRI findings are inconsistent in cases of LA and are not specific for LA [2,4,6].

Although ultrasonography (US) is the most popular imaging modality for the head and neck region, few studies have literatures addressed its utility for the evaluation of laryngeal pathologies because of critical limitations resulting from the soft tissue-air interface and laryngeal framework structures [8]. Moreover, there are no reports addressing US findings of LA.

Here, we report a case of LA mimicking laryngeal cancer, in which the diagnosis was facilitated by preoperative US and US-guided core-needle biopsy (US-CNB) prior to surgical biopsy. In addition, we introduce the US characteristic of LA, suggesting a possible role of US in preoperative evaluation.

CaseA 69-year-old female visited our clinic complaining of hoarseness for the past 4 months. She had no other signs or symptoms, such as cough, sore throat, dyspnea, dysphagia, or history of smoking or alcohol consumption. However, she had multiple comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, stage 3 chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and arterial fibrillation. Additionally, she had a recent history of myocardial infarction and had undergone coronary angiography with stent placement; she has been on anticoagulant medication since then.

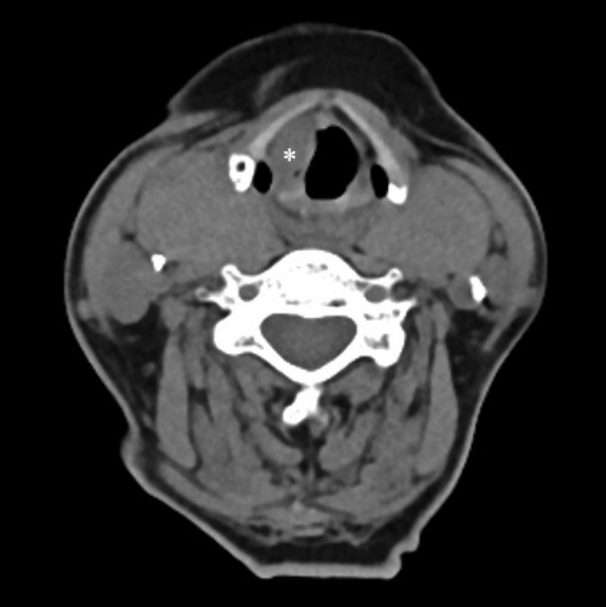

Laryngoscopy revealed a protrusion of the right false vocal cord with an irregular mucosal surface (Fig. 1). The ipsilateral vocal cords were edematous and immobilized. Due to impaired renal function, CT and MRI were performed without contrast enhancement. On the CT scan, a well-defined, homogenous, and low-attenuating mass without calcification was identified at the supralgottic region, and the mass extended to the glottic level through the paraglottic space (PGS) (Fig. 2). No suspicious lymph node enlargement was observed. The CT results suggested transglottic cancer involving PGS and with possible T3 stage. On MRI, the mass showed an intermediate signal on T1 and a high signal on T2, suggesting laryngeal malignancy on CT (Fig. 3). Based on the findings of laryngoscopy and cross-sectional images, we planned a suspension laryngoscopic biopsy under general anesthesia to confirm the pathological diagnosis of laryngeal cancer. However, because the patient was at a very high risk for general anesthesia owing to multiple comorbidities, laryngoscopic biopsy under general anesthesia was not possible. Hence, we attempted to use laryngeal US and subsequent US-CNB to evaluate her laryngeal mass, because her thyroid cartilage was not ossified. We used an HS70A US device (Samsung Medison, Seoul, Korea) with a high-frequency, linear, 3-12-MHz transducer with a setting of penetration mode. US clearly depicted the mass through the levels of the right supraglottis and glottis; it presented an ill-defined, homogenous, and isoechoic mass with an absence of internal vascularity (Fig. 4A), which was different from the US characteristics of laryngeal malignancy, usually presenting as a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass with increased vascularity. US-CNB was performed immediately via the transcartilage approach, and the specimen was harvested successfully (Fig. 4B). Pathological examination with hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed deposition of bright pink amorphous material in the extracellular space. Immunohistochemistry showed negative results for cytokeratin and positive results for Congo red staining and lambda light chain, ultimately leading to the diagnosis of amyloidosis. There was no evidence of systemic disease in additional laboratory and imaging studies. Approximately four months after diagnosis, laryngeal microsurgery using a CO2 laser was performed after maintaining multiple comorbidities, as the lesion gradually increased and hoarseness was aggravated accordingly. The lesion was completely removed by excision of the involved false cord and PGS, preserving the true vocal cord. Final pathological diagnosis was consistent with amyloidosis, concordant with the results of CNB. During the 12-months followup period, there was no evidence of recurrence.

DiscussionFor preoperative evaluation of amyloidosis, MRI has been reported to be an ideal modality by demonstrating an intermediate T1 signal, enhancement with contrast, and a low T2 signal [1,3,6]. However, the MRI findings in our case showed intermediate T1 and high T2 signals, which were not in accordance with these MRI characteristics and were confused with those of laryngeal cancer. In fact, because of the low incidence of LA, previous MRI findings of LA were based on the results of a limited number of cases; thus, these findings cannot be established as characteristic diagnostic feature. Moreover, the diagnostic performance of MRI in LA has not been verified. Indeed, several studies have reported MRI findings of LA different from the above-mentioned MRI findings, including a high T2 signal and/or marked enhancement with contrast on T1 [4,9]. Therefore, it should be noted that MRI findings of LA could vary and may not be diagnostic for preoperative suggestion of amyloidosis.

Conventionally, US examination has been considered to have a limited capacity for the evaluation of the larynx [10,11]. However, laryngeal masses in well-selected patients can be assessed with US through suitable anatomical windows, such as the suprahyoid regions, thyrohyoid membrane, and cricothyroid membrane [12,13]. Moreover, the utility of US can be enhanced unless the patient’s thyroid cartilage is completely ossified. However, US is significantly limited in depicting small or superficial lesions, which do not have sufficient volume to be detected by US, or in cases with ossified thyroid cartilage. In our case, fortunately, US could detect the lesion clearly along with the accurate disease extent involving the false cord and PGS because the lesion had sufficient volume and thyroid cartilage of the patient was not ossified. In addition, the US findings of our case (homogeneous isoechoic mass with smooth margin) were distinguishable from those of laryngeal cancer, which appears as a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass with irregular margins on US [14,15]. These US findings enable us to consider a diagnosis other than laryngeal cancer, suggesting that US could be used as a supplementary imaging modality to evaluate suspicious laryngeal masses mimicking laryngeal cancer.

Suspension laryngoscopic biopsy under general anesthesia is mandatory for the pathological diagnosis of LA. After pathological confirmation of LA with immunohistochemical staining, additional general anesthesia is required for therapeutic surgical intervention in most cases. However, in this case, amyloidosis was diagnosed using office-based percutaneous US-CNB, avoiding general anesthesia. Recently, several studies have reported the feasibility and results of office-based US-CNB for laryngeal and hypopharyngeal masses [10,12]. This technique is feasible in selected patients with a suitable tumor location and allows deep biopsy under real-time US monitoring, leading to accurate pathological diagnosis. Therefore, US-CNB could be a good alternative to avoid general anesthesia only for diagnostic procedure, particularly in patients with severe comorbidities and a high risk for general anesthesia. However, the operator should note that there is still a lack of established indications or guidelines of US-CNB for laryngeal mass. In addition, careful consideration should be paid to major bleeding/ hematoma at the larynx which can lead to serious medical situations even though it is extremely rare [10]. We always use Doppler US to identify vascular structures along the CNB path prior to the procedure to avoid major bleeding/hematoma and check the patient’s larynx 30 min after the procedure for early detection of any laryngeal swelling.

The primary treatment for LA is surgical removal or debulking, predominantly using microlaryngoscopy techniques [2]. However, given the organ involved it is often not possible to remove all the deposit. Hence, long-term follow-up is essential in all cases and recurrence is very common, usually observed in more than half of patients [3].

In conclusion, this case suggests a possible role of US in the evaluation of LA by facilitating tha differential diagnosis from laryngeal cancer prior to pathological diagnosis. Furthermore, subsequent US-CNB could provide a conclusive pathological diagnosis in patients with a suspicious laryngeal mass mimicking laryngeal cancer, avoiding general anesthesia for laryngoscopic biopsy. However, to demonstrate the usefulness and benefits of US for the evaluation of LA, more studies using US for this disease entity should be performed in the future, and we hope that this case would be the trigger for such exploration.

NotesAuthor Contribution Conceptualization: Dongbin Ahn. Data curation: Dongbin Ahn, Ji Hye Kwak. Formal analysis: Dongbin Ahn. Investigation: Dongbin Ahn, Ji Hye Kwak. Methodology: Dongbin Ahn, Jin Ho Sohn. Supervision: Dongbin Ahn, Jin Ho Sohn. Validation: Dongbin Ahn, Ji Hye Kwak. Visualization: Dongbin Ahn, Eun Jung Oh. Writing‚ÄĒoriginal draft: Dongbin Ahn, Eun Jung Oh. Writing‚ÄĒreview & editing: Dongbin Ahn, Ji Hye Kwak, Eun Jung Oh. Fig.¬†1.Laryngoscopy on adduction (A) and abduction (B) of the vocal cord shows a protruding mass (asterisk) with an irregular mucosal surface at the right false vocal cord.

Fig. 2.. CT demonstrates a well-defined, homogenous, and lowattenuating mass (asterisk) involving paraglottic space at the right supraglottic region.

REFERENCES1. Penner CR, Muller S. Head and neck amyloidosis: A clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Oral Oncol 2006;42(4):421-9.

2. Phillips NM, Matthews E, Altmann C, Agnew J, Burns H. Laryngeal amyloidosis: Diagnosis, pathophysiology and management. J Laryngol Otol 2017;131(S2):S41-7.

3. Burns H, Phillips N. Laryngeal amyloidosis. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;27(6):467-74.

4. Muneeb A, Gupta S. Isolated laryngeal amyloidosis mimicking laryngeal cancer. Cureus 2018;10(8):e3106.

5. Ng C, Mentias Y, Abdelgalil A. Imaging features of non-epithelial tumours of the larynx. Clin Radiol 2020;75(9):711.e5-12.

6. Parmar H, Rath T, Castillo M, Gandhi D. Imaging of focal amyloid depositions in the head, neck, and spine: Amyloidoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31(7):1165-70.

7. Georgiades CS, Neyman EG, Barish MA, Fishman EK. Amyloidosis: Review and CT manifestations. Radiographics 2004;24(2):405-16.

8. Law ST, Jafarzadeh SR, Govender P, Sun X, Sanchorawala V, Kissin EY. Comparison of ultrasound features of major salivary glands in sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72(10):1466-73.

9. Arslan A, Ceylan N, Cetin A, Demirci A. Laryngeal amyloidosis with laryngocele: MRI and CT. Neuroradiology 1998;40(6):401-3.

10. Ahn D, Lee GJ, Sohn JH. Time and cost of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy/core-needle biopsy for primary laryngohypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;164(3):602-7.

11. Xia CX, Zhu Q, Zhao HX, Yan F, Li SL, Zhang SM. Usefulness of ultrasonography in assessment of laryngeal carcinoma. Br J Radiol 2013;86(1030):20130343.

12. Ahn D, Lee GJ, Sohn JH, Lee JE. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology and core-needle biopsy for laryngeal and hypopharyngeal masses. Korean J Radiol 2021;22(4):596-603.

13. Beale T, Twigg VM, Horta M, Morley S. High-resolution laryngeal US: Imaging technique, normal anatomy, and spectrum of disease. Radiographics 2020;40(3):775-90.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|