|

|

AbstractBackground and ObjectivesTheory of Mind (ToM) refers to the ability humans have for recognizing the mental states of others and for predicting or explaining other people’s behavior. ToM is an essential ability people have for living with other people because it influences social relations, and the deaf children have been reported to have problems in ToM. As there are no ToM assessment tools in Korea, the purpose of this study was to establish such a version and to examine the early development of ToM of children with cochlear implant (CI).

Subjects and MethodThe original tools for ToM assessment were translated in Korean and the reliability and validity of the Korean version of ToM assessment tools were investigated with fifty normal hearing (NH) children. The early development of ToM of sixteen children with CI was compared with that of age-matched children with NH.

ResultsThe reliability of Korean version of ToM assessment tools was determined by tests for internal consistency and test-retest reliability. The validity of the tools was also evaluated by the tests for criterion-related validity and concurrent validity. There was no significant difference in ToM between children with CI and those with NH.

서 론인간은 사회적 동물이다. 타인과 관계를 맺는 것은 인간의 보편적인 기본 심리 욕구이기 때문에 인간은 홀로 삶을 영위할 수 없다[1]. 타인과 관계를 형성하고 유지하기 위해서는 타인과 원활한 의사소통이 가능해야 하고, 나아가 타인의 의도, 욕구, 믿음과 같은 정신 상태를 추측하고 타인의 행동을 이해하고 예측할 수 있어야 한다. 이와 같이 개인이 타인의 정신 상태를 추측하고, 행동을 이해하거나 예측하는 능력을 ‘마음이론(Theory of Mind, ToM)’이라고 한다[2].

마음이론은 Premack과 Woodruff [2]가 침팬지를 대상으로한 연구에서 처음 소개한 개념이다. 그들은 어떠한 훈련도 받지 않은 침팬지가 인간의 행동을 보는 것만으로 그 행동의 동기를 이해할 수 있다는 것을 확인하고, 타인의 마음 상태를 읽을 수 있는 추론 양식을 가리켜 마음이론이라고 명명하였다. 이후 마음이론은 발달심리학에서 ‘유아가 타인의 마음을 이해하는가’라는 주제로 활발하게 연구되었는데, 4세 무렵이 되면 타인의 마음을 분명하게 이해하고[3,4], 속임수나 풍자와 같은 고차원적인 마음이론은 학령기에 획득된다. 즉 마음이론은 아동기 전반에 걸쳐 지속적으로 발달하는 능력이다[5-7].

아동의 마음이론 발달이 사회성 발달과 서로 영향을 주고 받는다는 것이 여러 연구에서 보고되었다. 유아기 아동의 마음이론은 그들이 형성하는 또래관계에 영향을 미치고, 또래관계는 다시 더 높은 수준의 마음이론을 발달시키는 데 기여한다[8,9]. 마음이론이 부족한 아동은 좋은 또래관계를 형성하지 못해, 사회적 기술이 좋은 집단에 소속되지 못함으로써 마음이론을 지속적으로 발달시킬 기회를 얻지 못하게 된다[10,11]. 따라서 아동이 사회적 관계를 잘 형성하고 원만하게 유지하기 위해서는 연령에 맞는 마음이론을 갖추는 것이 중요하다.

난청 아동은 정상청력 아동에 비해 마음이론이 부족한 것으로 보고되었다. 한 연구에서는 건청 부모에서 태어난 난청 아동의 마음이론이 자폐성 장애 아동의 마음이론 만큼 나빴다고 보고하였다[12]. 또한 보청기를 착용한 난청 아동도 언어성과제는 물론 비언어성 과제를 사용하였을 때에도 정상청력 아동에 비해 마음이론이 심각하게 지연 발달하는 것으로 나타났다[13,14]. 인공와우이식 아동의 마음이론은 정상청력 아동에 비해 부족하다는 보고가 많지만[15-17] 유의한 차이가 없다는 보고도 있어[18,19] 연구 결과들이 일치하지 않으며, 아직 국내에서는 조기 인공와우이식 아동의 마음이론에 대해 보고된 바가 없다.

마음이론은 Hutchins 등[20,21]이 개발한 ToM-Task Battery (ToM-TB)와 ToM-Inventory(ToM-I)를 이용하여 평가할 수 있다. 이 두 가지 검사는 2~12세 사이 아동을 대상으로 마음이론을 평가하는 도구이다. 이 중 ToM-TB는 아동을 대상으로 마음이론을 직접 평가하는 도구이고 ToM-I는 아동의 마음이론을 부모 보고를 통해 간접적으로 평가하는 도구이다. ToM-TB와 ToM-I는 미국에서 표준화 과정을 거친 후 10여개의 언어로 번안되어 다양한 문화권에서 사용되고 있으나 국내에는 아직 소개되지 않았다. 이에 본 연구에서는 ToM-TB와 ToM-I를 한국어로 번안하고, 조기 인공와우이식을 통해 정상 언어능력을 획득한 아동의 초기 마음이론 발달을 알아보고자 하였다.

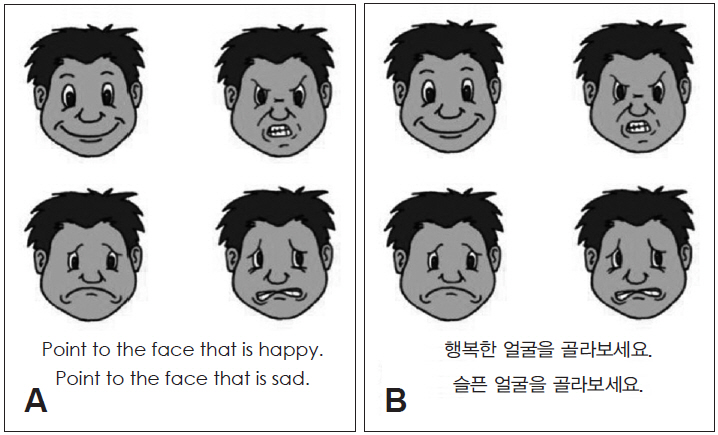

대상 및 방법마음이론 검사도구마음이론 검사도구는 ToM-TB와 ToM-I 두 가지 이다. ToM-TB는 아동을 대상으로 직접 평가하는 도구로서, 아동이 질문의 내용을 이해하는지를 점검하는 9개의 통제질문과 채점에 반영되는 15개의 평가질문으로 구성되어 있다(Table 1). ToM-TB는 이야기책 형식으로 구성되어 있다. 아동은 검사자가 제시하는 질문을 그림과 글자로도 함께 볼 수 있으며 검사자의 질문에 답하는 방식으로 검사가 이루어진다(Fig. 1). 아동이 평가질문에서 정반응 하였을 때 1점, 오반응 하였을 때 0점을 얻게 된다. 만일 평가질문을 제대로 이해했는지를 확인하는 통제질문에 대해 오반응을 보인 경우에는 질문을 제대로 이해하지 못하였으므로 평가질문에서 정반응 하더라도 점수를 얻지 못한다.

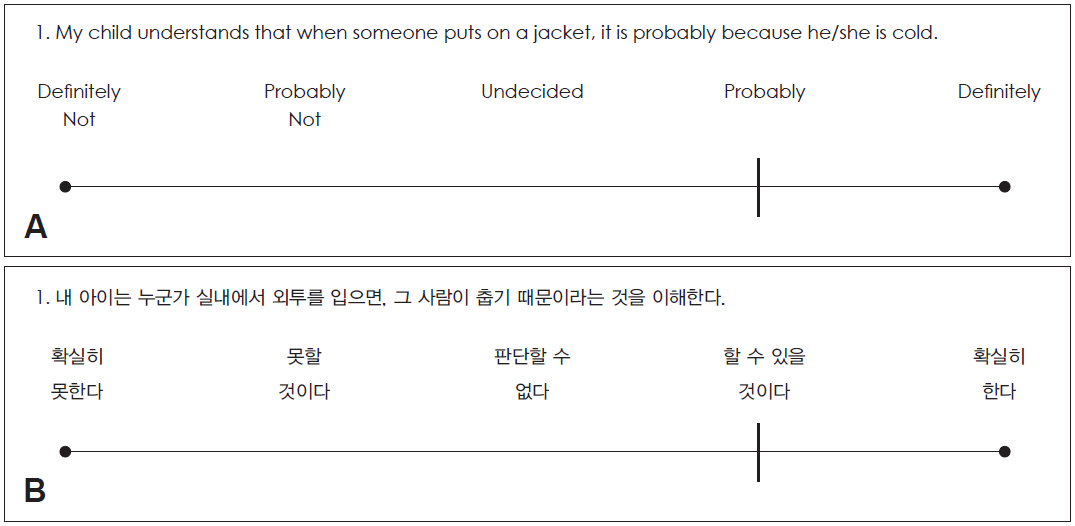

ToM-I는 아동의 마음이론을 부모 보고를 통해 간접적으로 평가하는 설문지 형식의 검사 도구이다. ToM-I는 아동의 마음이론을 묻는 질문 35문항, 기본 감정에 대한 이해능력인 정서인식(emotion recognition) 능력을 묻는 질문 10문항, 알다, 생각하다, 믿다와 같은 어휘에 대한 이해능력인 정신상태용어이해(mental state term comprehension)능력을 묻는 질문 6문항, 맥락 속에서의 언어사용능력을 의미하는 화용언어(pragmatics) 능력을 묻는 질문 9문항을 포함한 총 60문항으로 구성되어 있다(Table 2). 검사는 주 양육자가 아동의 수행력을 평가하는 방식으로 이루어지는데, 각 질문에 대해 0~20점으로 채점될 수 있는 연속적인 선에서 ‘확실히 못한다(definitely not), 못할 것이다(probably not), 판단할 수 없다(undecided), 할 수 있을 것이다(probably), 확실히 한다(definitely)’의 5가지 수준을 기준으로 아동에게 해당된다고 생각되는 지점에 표기하도록 하고 소수점 1단위까지 점수에 반영한다(Fig. 2).

한국어 마음이론 검사도구 번안ToM-TB와 ToM-I의 번안은 두 가지 검사도구의 원 개발자인 Hutchins 박사에게 Theory of Mind Inventory Advisory Board에서 요구하는 번안과 타당화 계획에 대한 제안서를 보내어 한국어 번안에 대한 공식적인 권한을 부여받은 후 시행하였다.

언어병리학 석사 이상의 언어치료사 3인이 영문 검사도구를 각각 번역한 후 취합하여 일차 번안본을 만들었고, 이것을 영어 한국어 이중 언어 사용자가 역번역하였다. 역번역자는 원어민과 함께 원본과 역번역본이 의미상 차이가 없는지 검토하는 과정을 거쳤다. 번역 과정에서 우리 문화에 비추어 어색한 문항은 원문항에서 측정하고자 하는 바를 나타냄과 동시에 우리 문화에 적용 가능한 표현으로 바꾸었으며, 이 경우 원개발자와 교신하여 개념적 동등성을 유지하였다.

원개발자와 상의하여 우리 문화에 적합한 표현으로 내용을 바꾼 문항은 ToM-I에 포함된 두 문항으로 관용어구와 말놀이 이해 능력을 측정하는 문항이었다. 관용어구 이해능력을 측정하는 원문항은 “If I said “Let’s hit the road!” my child would understand that I really meant “Let’s go!””인데, “Let’s hit the road”가 “Let’s go”와 동일한 뜻이라는 것을 이해하는지를 묻는 내용이었다. 번안본에는 우리나라 6~8세 아동이 이해한다고 보고된 관용어 중에서 관용어의 특성을 잘 반영하면서도 가장 쉽다고 판단되는 관용어를 채택하여 “식은 죽 먹기”를 “매우 쉽다”로 이해하는지를 묻는 내용으로 수정하였다[22]. 말놀이를 측정하는 원문항은 “If I said “What is black, white and ‘read’ all over?” “It’s a newspaper!” my child would understand the humor in this play on words.”이다. 이는 아동이 이러한 유머를 이해하고, read가 색깔 red와 같은 발음이라는 것을 이해해야 하는 내용이었다. 우리 언어에서는 의태어, 의성어, 관용어, 감탄어, 사자성어와 같이 언어유형에 따라 다양한 말놀이가 존재하지만 이러한 말놀이 중에서도 가장 쉽고 원문항에서 측정하고자 하는 바와 동일한 ‘발음의 유사성’에 대한 이해를 담고 있는 말놀이를 채택하여 번안본에는 “세상에서 가장 빠른 닭은 후다닥”이라는 수수께끼를 이해하는지를 묻는 내용으로 수정하였다[23].

번안본은 아동가족학과 교수 1인과 경력 5년 이상의 언어치료사 3명, 2~12세의 자녀를 키우고 있는 어머니 7명에게 문항의 내용이 측정하고자 하는 바와 일치하는지와 번안된 문항의 내용이 명료하게 전달되는지에 대한 피드백을 받고 최종본을 완성하였다.

한국어 마음이론 검사도구의 신뢰도와 타당도 검증한국어로 번안된 ToM-TB의 신뢰도와 타당도 검증은 청력이 정상이고 청각 관련 질환의 병력이 없으며 언어평가에서 정상 언어능력을 가지고 있는 50명의 아동을 대상으로 시행하였다(Table 3). 한국어 ToM-I의 신뢰도와 타당도 검증은 정상 청력 아동의 보호자 32명을 대상으로 하였다(Table 4).

한국어로 번안된 두 가지 마음이론 검사도구의 신뢰도는 문항의 내적 일치도(internal consistency)와 검사-재검사 신뢰도(test-retest reliability)를 통해 검증하였다. 내적 일치도는 동일한 구인을 재고 있는 문항들이 어느 정도의 동질성이 있는지를 확인하는 것이다. 검사에 포함된 문항 하나하나를 모두 독립된 한 개의 검사로 생각하여 검사 문항들 간의 합치도, 동질성, 일치성을 종합하는 신뢰도로, 피험자들이 각 문항에 얼마나 일관성 있게 반응하였는지를 파악함으로써 검사의 신뢰도를 추정하는 방식이다. 내적 일치도는 문항의 일관성을 나타내는 계수인 Cronbach α 계수로 신뢰도를 추정하는데 Cronbach α는 0부터 1의 값을 가지며 값이 클수록 신뢰도가 높다. 0.7 이상이면 바람직하고 0.8 이상이면 신뢰도가 매우 높은 것으로 본다. 검사-재검사 신뢰도는 동일한 검사를 같은 개인에게 두 번 실시하여 검사 점수의 상관계수를 통해 신뢰도를 검증하는 방식이다.

마음이론 검사도구의 타당도는 준거타당도와 공인타당도를 이용하여 검증하였다. 준거타당도는 아동의 연령에 따른 발달을 측정하는데 타당한 검사인지를 알아보기 위한 것으로 아동의 생활연령과 마음이론 검사점수와의 상관관계를 알아보았다. 공인타당도는 이미 타당성이 검증된 기존 검사와의 상관관계를 통해 해당 검사의 타당도를 검증받는 방식으로, 한국에서 표준화 과정을 거쳐 널리 사용되고 있는 수용표현어휘력검사(Receptive Expressive Vocabulary Test, REVT) 점수와 마음이론 검사 점수의 상관관계를 살펴보았다. 통계처리는 SPSS(version 23; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA)로 시행하였다.

인공와우이식 아동의 초기 마음이론 발달인공와우이식 아동의 초기 마음이론 발달을 알아보기 위해 인공와우이식 아동과 정상 청력 아동을 대상으로 한국어 마음이론 검사를 시행하고 점수를 비교하였다. 인공와우이식 아동군은 선천성 농으로 3세 이전에 이식 수술을 받고 인공와우 사용 기간이 3년 이상이며 중복장애와 심한 내이기형이 없는 아동 16명이 포함되었다. 남자가 8명, 여자가 8명이었으며, 검사 시행 당시 연령은 평균 74.56개월(표준편차 11.38)이었다. 인공와우이식 아동 16명 중 14명은 순차적 인공와우이식을 받아 양측 인공와우를 사용하고 있었다. 건청 대조군은 인공와우이식 아동과 성별 및 연령(±3개월)이 일대일로 동일한 정상 청력 아동 16명이었다. 인공와우이식 아동과 정상 청력 아동 간 생활연령과 언어능력은 통계적으로 유의한 차이가 없었다(Table 5).

본 연구는 동아대학교병원 임상연구심의위원회의 승인을 받은 후 전향적으로 진행되었으며, 연구에 참여한 모든 대상자로부터 연구 참여에 대한 동의서를 받은 후 시행하였다(DAUHIRB-17-097).

결 과한국어 ToM-TB와 ToM-I의 신뢰도한국어 ToM-TB 검사 15문항 전체에 대한 Cronbach α 계수는 0.835였고, 한국어 ToM-I 검사 60문항에 대한 Cronbach α 계수는 0.974로 두 검사 모두 매우 높은 내적 일치도를 보였다. 검사-재검사 신뢰도 검증에 참여한 아동은 9명이었고, 2회 시행한 검사 점수의 상관계수는 ToM-TB가 0.975(p<0.01), ToM-I가 0.986(p<0.01)으로 매우 높은 검사-재검사 신뢰도가 있는 것으로 확인되었다.

한국어 ToM-TB와 ToM-I의 타당도한국어 ToM-TB 검사와 한국어 ToM-I 검사 모두에서, 검사 당시 아동의 연령과 검사 점수 간에 강한 양의 상관관계를 보여 이 두 가지 검사는 준거타당도가 있는 것으로 확인되었다. 또한 아동의 REVT 점수와 두 가지 한국어 마음이론 검사 점수도 강한 양의 상관관계를 보여 두 가지 검사의 공인타당도가 확인되었다(Table 6).

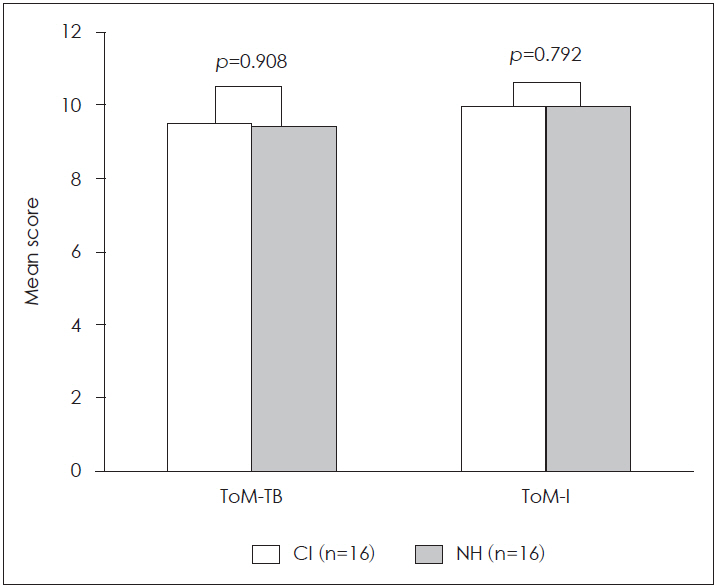

인공와우이식 아동의 초기 마음이론 발달한국어 ToM-TB 점수는 인공와우이식 아동군과 정상 청력 아동 군 간에 유의한 차이가 없었다(p=0.908). 한국어 ToM-I 점수도 두 군 간에 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았다(p=0.792)(Fig. 3).

고 찰본 연구는 한국어 마음이론 검사도구를 확립하기 위해 시행되었다. 이를 위해 저자들은 영문 마음이론 검사도구를 한국어로 번안하고 신뢰도와 타당도를 검증하였다. 번안 과정에서 동시번역, 역번역 등의 번안 절차를 준수하였고 문화적 동등성을 유지하였으며, 통계적 방법을 이용하여 한국어 마음이론 검사도구의 신뢰도와 타당도를 검증하였다. 이로써 마음이론을 측정할 수 있는 한국어 검사도구가 마련되었다.

마음이론은 타인의 마음 상태를 이해하는 능력이다. 여러 연구를 통하여 유아도 마음이론을 가지고 있어, 타인의 마음과 행위의 관계를 이해한다는 것이 입증되었다[3,4]. 유아기에 형성된 초기 마음이론은 더 복잡한 고차위 마음상태를 이해하는 기초가 되며, 아동이 형성하는 또래관계에 중대한 영향을 미친다[8,9]. 또래관계는 아동이 맺는 첫 사회적 관계이며 학교 적응을 결정하는 중요한 요인이다[24]. 초기 마음이론의 결함은 또래관계 형성을 어렵게 하고 학교 부적응을 초래할 수 있기 때문에[25], 유아기부터 마음이론이 잘 발달하고 있는지 살펴볼 필요가 있다.

인공와우이식 아동을 대상으로 한 기존의 많은 보고들은 말지각력, 말명료도, 그리고 언어능력 등을 인공와우이식의 효과와 청각재활의 성공 여부를 판단하는 지표로 사용하고 있으며, 조기 인공와우이식을 시행하고 적절한 청각재활치료를 받은 경우에는 정상 혹은 정상에 가까운 구어의사소통능력을 획득하는 것으로 보고하고 있다[26-28]. 하지만 조기 청각재활의 궁극적인 목표가 구어의사소통능력 획득에 기초한 일반 구어 사회로의 성공적인 통합이라는 점을 고려하면, 구어의사소통능력 획득 여부 외에 아동의 사회정서적 능력을 평가하는 추가적인 검사도구가 필요하다. 이런 측면에서 본 연구에서 소개한 마음이론 검사도구는 인공와우이식 아동의 사회정서적인 적응 능력을 살펴볼 수 있는 좋은 도구라고 할 수 있다.

본 연구에서 3세 이전에 인공와우이식을 받고 자신의 생활연령에 적합한 언어능력을 획득한 학령전기 인공와우이식 아동의 마음이론은 정상 청력 아동의 마음이론과 비교하여 유의한 차이가 없었다. 이러한 결과는 인공와우이식 아동의 조기 중재의 효과가 언어능력 발달에 국한되지 않고 사회정서적 측면에서도 정상적인 발달을 유도하고 있음을 보여준다고 할 수 있다. 학령전기 마음이론은 초기 마음이론인 만큼, 이후 학령기와 청소년기에 발달하는 고차위 마음이론에서도 정상 청력 아동과 유사한 발달을 보일지 후속 연구를 통해 살펴볼 필요가 있다. 또한 마음이론을 임상에서 사용하기 위해서는 연령별 정상치 규준이 필요하기 때문에 정상치 규준 설정을 위한 후속 연구를 시행할 계획이다.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis work was supported by NRF (National Research Foundation of Korea) Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2016-Fostering Core Leaders of the Future Basic Science Program/Global Ph.D. Fellowship Program).

Fig. 1.An example of ‘Theory of Mind-Task Battery.’ This is a task 1 which asks basic emotion recognition. A Child can answer with words or point to the answer. Original version (A) and Korean version (B).

Fig. 2.An example of ‘Theory of Mind-Inventory.’ This is an item 1 which asks physiologically-based behavior. Parents evaluate their child performance by making a vertical line wherever they want on the line of continuum. Original version (A) and Korean version (B).

Fig. 3.Comparisons of ToM between children with CI and those with NH. There was no significant difference between two groups in ToM-TB and ToM-I. ToM-TB: Theory of Mind-Task Battery, ToM-I: Theory of Mind-Inventory, CI: cochlear implant, NH: normal hearing.

Table 1.The subscale of ‘Theory of Mind-Task Battery’ Table 2.The subscale of ‘Theory of Mind-Inventory’ Table 3.Demographic data of children with normal hearing who attended the tests of reliability and validity of the Korean version of Theory of Mind-Task Battery Table 4.Demographic data of children with normal hearing who attended the tests of reliability and validity of the Korean version of Theory of Mind-Inventory

Table 5.Demographic data of children with CI and age-matched children with NH REFERENCES1. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000;55(1):68-78.

2. Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav Brain Sci 1978;1(4):515-26.

3. Martin JD. Theory of mind: how children understand others’ thoughts and feelings. 1st ed. Seoul: Hakjisa Publisher; 2013. p. 13-359.

4. Wellman HM, Cross D, Watson J. Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: the truth about false belief. Child Dev 2001;72(3):655-84.

5. Repacholi BM, Gopnik A. Early reasoning about desires: evidence from 14- and 18-month-olds. Dev Psychol 1997;33(1):12-21.

6. Astington JW, Pelletier J, Homer B. Theory of mind and epistemological development: the relation between children’s second-order falsdbelief understanding and their ability to reason about evidence. New Ideas Psychol 1995;20(2-3):131-44.

7. Happé FG. An advanced test of theory of mind: understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. J Autism Dev Disord 1994;24(2):129-54.

8. Caputi M, Lecce S, Pagnin A, Banerjee R. Longitudinal effect of theory of mind on later peer relations: the role of prosocial behavior. Dev Psychol 2012;48(1):257-70.

9. Slaughter V, Dennis MJ, Pritchard M. Theory of mind and peer acceptance in preschool children. Br J Dev Psychol 2002;20(4):545-64.

10. Fink E, Begeer S, Peterson CC, Slaughter V, de Rosnay M. Friendlessness and theory of mind: a prospective longitudinal study. Br J Dev Psychol 2015;33(1):1-17.

11. Peterson CC, O’Reilly K, Wellman HM. Deaf and hearing children’s development of theory of mind, peer popularity, and leadership during middle childhood. J Exp Child Psychol 2016;149:146-58.

12. Peterson CC, Siegal M. Changing focus on the representational mind: Deaf, autistic and normal children’s concepts of false photos, false drawings and false beliefs. Br J Dev Psychol 1998;16(3):301-20.

13. Peterson CC. Theory-of-mind development in oral deaf children with cochlear implants or conventional hearing aids. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45(6):1096-106.

14. Figueras-Costa B, Harris P. Theory of mind development in deaf children: a nonverbal test of false-belief understanding. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ 2001;6(2):92-102.

15. Ketelaar L, Rieffe C, Wiefferink CH, Frijns JH. Dose hearing lead to understanding? Theory of mind in toddlers and preschoolers with cochlear implants. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37(9):1041-50.

16. Sundqvist A, Lyxell B, Jönsson R, Heimann M. Understanding minds: early cochlear implantation and the development of theory of mind in children with profound hearing impairment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78(3):538-44.

17. Roh J, Yim D. Relationships between reading comprehension and mind-reading in children with cochlear implants from fourth through sixth grades. Commun Sci Disord 2013;18(2):183-93.

18. Remmel E, Peters K. Theory of mind and language in children with cochlear implants. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ 2008;14(2):218-36.

19. Ziv M, Most T, Cohen S. Understanding of emotions and false beliefs among hearing children versus deaf children. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ 2013;18(2):161-74.

20. Hutchins TL, Bonazinga LA, Prelock PA, Taylor RS. Beyond false beliefs: the development and psychometric evaluation of the perceptions of children’s theory of mind measure-experimental version (PCToMM-E). J Autism Dev Disord 2008;38(1):143-55.

21. Hutchins TL, Prelock PA, Bonazinga L. Psychometric evaluation of the Theory of Mind Inventory (ToMI): a study of typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2012;42(3):327-41.

22. Kim HJ. A comparison of idiom comprehension ability of school age ADHD children and normal children [dissertation]. Yongin, Yong-In Univ.; 2008.

23. Kwak EH. A study of the formation process behind modern Korean riddles. Hangeul 2013;302:223-45.

24. Coolahan K, Fantuzzo J, Mendez J, McDermott P. Preschool peer interactions and readiness to learn: Relationships between classroom peer play and learning behaviors and conduct. J Educ Psychol 2000;92(3):458-65.

25. Barnow S, Lucht M, Freyberger HJ. Correlates of aggressive and delinquent conduct problems in adolescence. Aggress Behav 2005;31(1):24-39.

26. Blamey PJ, Sarant JZ, Paatsch LE, Barry JG, Bow CP, Wales RJ, et al. Relationships among speech perception, production, language, hearing loss, and age in children with impaired hearing. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2001;44(2):264-85.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|